In this guide to a pain free squat you will find all the information about squatting you could ever want to know. Including:

- Your guide how you should squat (and why your squat is different to the person next to you at the gym)

- What to do if you’re getting pain when you squat

- An understanding of the amazing differences in our anatomy and how this effects our squatting

- My favourite types of squats

Before we get started, if you’re having trouble squatting why not book in for a free telehealth session with me?

Why Is The Squat Important?

Why you need to have a pain free squat is different for every person.

A volleyballer might say it is important to lower themself quickly to return a spike.

For a manual worker, their job might require repetitive lifting of heavy loads from the ground.

If you ask my nanna, she might not tell you that squatting is something she is struggling with. But ask her about getting up and down from her chair and she will let you know all about it. Being unable to squat or squat pain free is linked with a fear of losing her independence. We all have to squat!

There is no doubt squatting is an essential daily activity (try sitting on the toilet without squatting) and experiencing pain during squats can be disabling.

In this article, we will explore the science of squats and how to optimise your squat and return to pain-free squatting.

How To Squat Pain Free? The Basics

Mechanically speaking to squat the centre of mass of our body (about your belly button) has to rise and fall over our base of support (feet). We need to be able to do this without moving that centre of mass too far forwards or backwards over our base otherwise we would fall over.

Just like there are many roads to Rome, there are also many ways to squat.

But not all would suit you.

Why? Because you’re beautiful and unique and maybe even a little bit weird? Maybe you’ve got a deep acetabulum.

Not sure what that means? We will have an in-depth discussion further in this article.

Squatting Over Your Lifetime

If you consider the squatting ability of a person through a lifetime, you notice that it is something we gradually lose.

Let’s look at children. They don’t put much thought into squatting. If fact, it is not uncommon that you see them drop into a deep squat like a sack of rice on the kitchen floor.

Next we have olympic weightlifting athletes. Absolute specimens of humanity who are capable of carrying an incredible amount of load in challenging positions without breaking a sweat!

Finally, with the inevitability of aging, as we turn old and grey, a simple task like sitting down can become dangerous and near impossible. As we squat to lower ourselves into our comfy chairs we find it a struggle to stay upright. We need to hold dearly to the arm rails and eventually flop into the chair half-way through a quarter squat.

What is lost is the mobility and strength that is necessary for control of movement when squatting. It can be really difficult to get this back and complete a pain free squat but it’s definitely worth it.

Mobility For Squatting

As physiotherapist I get a lot of questions about pain free squats like these from my clients:

“Should my knees go over my toes?”

“How far should my feet be apart?”

“Should I point my toes out?”

“Is squatting bad for my knees?”

“How deep should I go during a squat?”

“Dominic how much steel can you squat?”

You might be surprised but there is no “one size fit all” answer to that! The optimal squat is different for everyone!

We all squat differently due to anatomical variations and differences in mobility.

Anatomical Variations

There is a wide variation in the anatomy of our hips and legs that have huge implications to how we must squat.

- The angle of the neck of the femur

- The angle of the acetabulum

- Femoral angle of torsion

- The shape of the head of the femur/ acetabulum

- The length ratio of tibia, femur and torso

- Differences or asymmetry left vs. right side of your hip

Hip Angles

With a neck of femur that is more vertical (coxa valga) or a lateral facing acetabulum, you are most likely to experience a bony block when squatting with a narrow stance.

If your ankle of your femoral neck or acetabulum is varied from normal, adopting a wider stance, will provide greater range and ease of movement when you attempt your pain free squat.

Hip Twist & Torsion

Usually the head of the femur is around 8-14 degrees forward-facing. If angled further forwards than this if is considered a presentation of femoral anteversion.

On the other hand (or hip), it can also be angled further backwards which is known as femoral retroversion.

These structural differences in femoral head angulation may result in differences in foot position during squats. If you have excessive femoral anteversion you are more likely to toe-in while those with femoral retroversion are more likely to toe-out.

Considering the wide variation in structural and biomechanical differences across the population, the commonly heard cue to squatting “feet shoulders width apart, parallel and pointing forward” recommendation does not work for all.

The Shape Of Your Hip Joint

The hip joint is made up of the acetabulum (the socket) and the head of the femur (the ball). The range of movement our hip joints allow is varied when the rim of the acetabulum extends beyond normal and/or there is excessive convexity of the femoral head.

It can result in premature contact between the hip joints during end range movement resulting in reduced joint range of motion, especially hip flexion and internal rotation.

What About The Legs When Squatting?

As I explained earlier, we have to keep our centre of mass over our feet to maintain our balance during a pain free squat. However, you might be surprised that two people of the same height and size can look drastically different when they squat. This is due to our different body proportions. We are so unique that people who have the same height, even the same length legs can squat differently if they have longer or shorter upper or lower leg sections.

Take a look at this table.

| Torso | Femur | Tibia | Outcome | |

| Long | Short | Long | Upright trunk, deep squat | Feel more quads |

| Short | Long | Short | Bend over, near-parallel squat | Feel more lower back muscles & glutes. Falling over if go any deeper |

This table addresses some of the commonly asked questions such as “what should a squat look like?” and “how deep should I go?” The reality is how your squat looks, how deep you can go is determined by your own unique build!

So instead of trying to squat all the way to the ground you should squat to your own profile. It is pointless to try to achieve something that you are not structurally built to do.

If you’re someone who has a short torso, long femur and short tibia; you probably hate squats! You would probably consider squatting a “ lower back exercise” rather than a leg exercise.

For an athlete or powerlifter who is built like this, modifications can help to improve your squat.

Adopting a low bar squat or wide stance can be beneficial by reducing the leverage on the lower back hence reducing the strain. A heel lift (from a podiatrist) that allows the knee to come further forward and maintain a more upright trunk is also beneficial.

If your goal is to strengthen your legs you will find exercises such the leg press to be a great alternative option without excessive straining on your back.

Joint And Soft Tissue Mobility

This might be obvious, but for anyone to execute a squat, the knees have to come forward and the hips have to move back. More than anything else, it is the limitation in ankle mobility that is most likely to influence the quality of the squat.

To illustrate this, let’s use the example of a parallel squat, a position most people are able to achieve.

Imagine holding a parallel squat with 20 degrees vs 45 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion.

In the first position, you shin would be more upright, your hips further back and your trunk has to be bend over in order to maintain balance.

In contrast, in the second position with a greater ankle dorsiflexion your knee would be further forward and your trunk would maintain a more upright position.

Mechanically, the first position is more demanding for the back and hip muscles. Whereas in the second position, it’s more demanding for your quads.

Your ankle mobility effectively influences whether you are more knee or hip dominant when performing a squat.

Limitation in ankle mobility can be due to stiffness in the ankle joint, tightness of the connective tissues or the makeup of your foot bones. Just like how our hips can all be different shapes, so are the bones in our feet.

If you feel a “pinch” at the front of the ankle when you try to squat this indicates a joint restriction. Mobilisation of the ankle joint with a physio sports massage might provide some benefit.

Alternatively, the use of a heel lift can be used to facilitate movement at the ankle improve the leverage when squatting.

Tightness that is felt in the calf muscle or Achilles tendon indicates soft tissue restrictions. Eccentric loading exercises like calf raises and dips are effective ways to improve ankle dorsiflexion and the quality of your squat.

Higher up in the kinetic chain, reduced mobility in the thoracic region of the spine can also overload the lower back and affect hip motion. In order to remain upright with a hunched back, the lower back has to arch more. This overloads the lumbar erectors muscles.

In addition, the excessive activation of the erectors muscles can tilt the pelvis forward. This can increase compression of the front hips.

Movement Control

Trunk control

The body is supported by both passive and active structures during static and dynamic movements. During loaded squats or a lifting activity we are often told to keep our backs straight.

The thinking is that “keeping our back straight” helps engage the back muscles, prevents us from rounding our lower back and straining those passive structures of our back that could lead to injury.

All sounds fair enough – there is some evidence that flexion and rotation of the lower back is often a mechanism of lower back injury.

But, sometimes the idea of what a straight back is can get misinterpreted. At the gym I’ll often hear coaches yell “arch that back!’’.

The intention is to avoid something like this

Unfortunately, this can be misinterpreted and go too far as keeping an excessive arch in the lower back or an anterior pelvic tilt is not ideal either. In fact, it is a setup problem that can result in overloading of the lumbar erector muscles, pinching on the anterior hip and the infamous butt wink (rounding of the lower back at the bottom of a squat).

All of these can contribute to back and hip pain.

The ideal position is to maintain a neutral lower back. This is usually a slight natural curve while maintaining an active co-contraction of your abdominal and back muscles when lifting heavy loads.

If you find this difficult, exercise that helps you dissociate your hip and back to might be beneficial.

Try this exercise!

Lay in a crook lying position. Position your feet close to your bottom. Gradually tuck your tail bone up, feeling for contractions of your abdominal, back and glute muscles. Maintain a slight arch in the lower back and slowly lift your bottom up while maintaining the relative position of your pelvis to your trunk.

You’ve just found your neutral spine position which will help you when performing a pain free squat.

The Ugly Squat

I’m sure you have seen those guys and girls with the ugly squats! Even some legends like Michael Jordan do it!

So is squatting ugly a good thing to do?

When searching for a pain free squat I generally don’t recommend it! However, you might be surprised that there are some studies that found biomechanical advantages to using the ugly squat to produce more power! We will save the discussion for that for another day though.

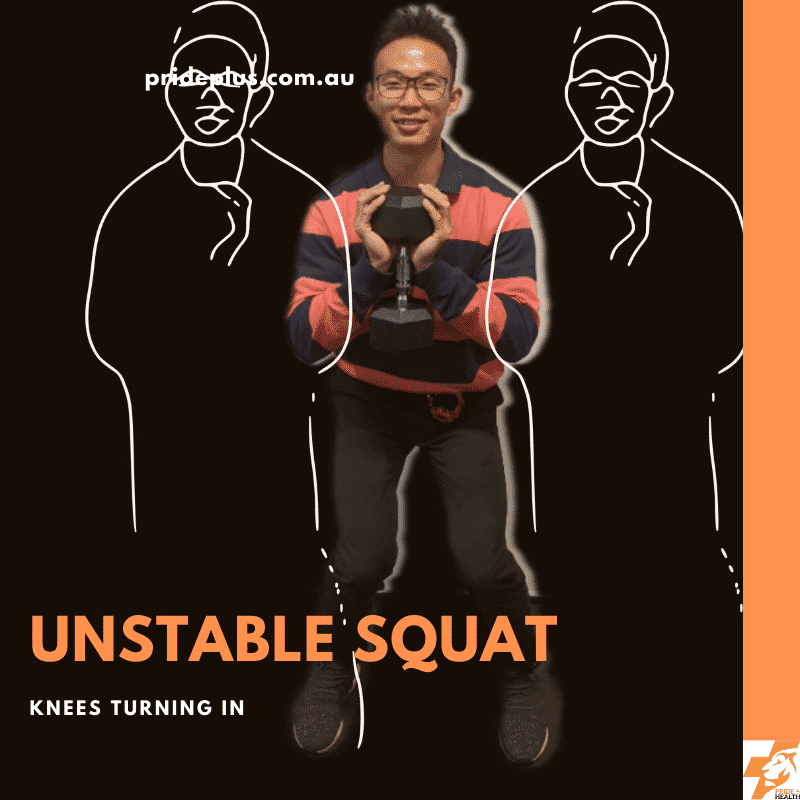

Scientifically the movement pattern observed in the ugly squat is referred to as dynamic valgus. It is characterised by excessive hip adduction and internal rotation, knee abduction and ankle eversion during a squatting movement.

In general, it is a movement pattern that is discouraged as it is linked to knee pain, ACL tears and even hip pain.

There are many factors contributing to a dynamic knee valgus. They can be categorized into proximal, local, distal or combination issues

- Proximal issues

- Weakness of the Hip

- Poor control of Hip

- Local Issues

- Tightness of the lateral knee structures

- Laxity of the medial knee structure

- Poor quadriceps muscles balance

- Distal issues

- Weakness/ poor control of ankle invertors

- Stiff ankle joints

- Tight calf muscles

Before you troubleshoot your ugly squat, it is important to figure out which is the primary issue before deciding if mobility, strengthening or coordination or orthotics may be needed.

A simple test you can perform is to stand with your usual comfortable stance. For most people, the feet are planted passively on the ground.

Instead, try this!

When squatting maintain your foot position, but imagine you are spreading onto the ground in an outwardly fashion. This will help recruit the muscles that are weak or often neglected.

You will notice lifting of the arches on your feet, increased activation of your quads and glutes. Only squat as deep as you can maintain this.

If that helps you feel more stable or reduce your pain, it indicates that there is more work to be done!

Pathological States Affecting Squating

Some pathological states can also result in the development of pain or injury during a squat. Some common conditions include the following

Spondylolisthesis

- Slippage of the vertebral at the lower back

- Commonly asymptomatic

- In symptomatic population, repetitive loading of the lower back through extension may cause further structural stress resulting in lower back pain or stress fracture of the pars interarticularis

- Improving hip, thoracic and lower quarter strength would reduce extension load to the symptomatic segment

Hypermobility Disorders

- A connective tissue disorder that results in joint laxity

- Knee pain is a common complaint and can be exacerbated by activity

- End range loading on passive restraining structures ( I.e knee hyperextension, flexible flat foot), muscle weakness and poor proprioception is a common feature of people with hypermobility disorder.

- Repetitive end range loading can lead to painful conditions.

- For instance, hyperextension at the knee is associated with fat pad impingement

- Retraining control of movement through range would be beneficial in improving pain

Traumatic Knee Injuries

- The ligaments of the knee such as the ACL, MCL, LCL and PCL are passive restraints to the knees. They provide stability to the knee by limiting excessive movements between the knee joints when huge forces pass through the knee either due to muscular contractions or external load.

- The meniscus, on the other hand, is a congruent structure with shock-absorbing qualities that facilitate smooth tracking of the knee and helps in the absorption of impact.

- Optimising movement after such injuries and avoiding the ugly squats and the likes would be the key to extending the longevity of the knee.

- With active rehabilitation that includes mobility, proprioceptive, strength and balance training, it is possible to regain pain-free motion.

Femoral Acetabular Impingement (FAI)

- A condition in which extra bone grows along the acetabulum, neck of femur or both — giving the bones an irregular shape.

- Such morphology of hip structure is fairly common and can be present in people without hip symptoms.

- However, in some individuals, participation in activities that involve repetitive end range loading of joint structures can reproduce pain.

- Symptoms include hip/groin pain related to certain hip movement or position.

- It is recommended that such individuals avoid pain provocative movements such as deep hip flexion, hip adduction and internal rotation.

- Optimising the mobility of the lower extremities, spine and strengthening of the deep hip muscles improve hip symptoms.

Osteoarthritis

- People with osteoarthritis often complain of painful hips and knee on squatting.

- However, it is important to recognise that with OA, pain does not mean harm. In the past, the condition was thought to be attributed to “wear and tear”. However, increasing amounts of evidence show that osteoarthritis is part of the process of joint reparation.

- Pain during activity is due to increased sensitivity to stimulus rather than damage.

- Studies have found that resistance training over an extended period provides improvement in pain and function in people with arthritis

- Load management and ensuring the symptoms is well tolerated during rehab is the key to success

- Where the joints are sensitive to high compressive load your physiotherapist can offer you alternative options that can be better managed including

- open kinetic chain exercises leg extension exercises

- isometric knee extension exercise

- Heavy resistance (3-5 RM) exercise elicits better improvement in strength compared to lower resistance & high repetition exercises

- The current guidelines recommend the following for people with OA

- 25-45 reps per muscle group per week for regular population

- 50+ reps a week for athletic population

- At least twice per week

- Squats are a challenging exercise and they’re likely to provide transferable gains to daily activities

Osteoporosis

- Osteoporosis is a disease characterised by a decrease in bone density.

- It is a disorder in which bones become increasingly porous and brittle leading to increased risk of fracture.

- 2.2 million Australians are affected by osteoporosis.

- About 11% of men and 27% of women aged 60 years or more are osteoporotic

- In Australia the lifetime risk of osteoporotic fracture after 50 years of age: 42% in women, 27% in men.

- While exercise has been shown to maintain or even improve bone density in this population, caution must be taken when selecting exercises.

- High intensity, high force and weight-bearing resistance exercises have been shown to be beneficial for individuals with mild-moderate osteoporosis

- However, for individuals in the lower end of the spectrum, with very low bone density High-intensity interval training may be contraindicated.

- Extra caution should be taken for those with a history of stress fracture, dowager’s hump, height loss.

- If unsure, always start slow and seek the advice of a physio or EP (exercise physiologist)

I Am Getting Pain From Squatting; What Should I Do?

Pain arises when you load yourself beyond the capacity of the tissues. To get a pain free squat ask yourself these questions

- Am I setting myself right for my build?

- Consider whether your starting positions or movement over stressing passive structures

- Is my mobility resulting in overload to specific structure?

- Consider a squat variation that suits your mobility

- Goblet squat

- Front squat

- Low bar squat

- High bar squat

- Stretch/mobilise before exercise

- Consider equipment modifications like heel wedge or orthotic

- Consider a squat variation that suits your mobility

- Do I have a problem controlling my movements?

- If the answer is yes consider if it is due to

- Weakness

- Coordination

- Poor mobility

- If no

- You could just be overloading excessively, take some time to improve your capacity by strengthening up

- If the answer is yes consider if it is due to

- Is there a pathological state causing my pain?

This checklist is something I work through in clinic with my clients who are having pain when they are squatting. If you’re in need of some personal assessment and guidance you can book in with me and our physiotherapy team in Pascoe Vale.

Also, do you get sore knees? We have a new completely online physio program for knee pain. Check it out.

References

Hewett, T. E., Myer, G. D., Ford, K. R., Heidt Jr, R. S., Colosimo, A. J., McLean, S. G., … & Succop, P. (2005). Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: a prospective study. The American journal of sports medicine, 33(4), 492-501.

O’Sullivan, P. (2005). Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Manual therapy, 10(4), 242-255.

Dierks, T. A., Manal, K. T., Hamill, J., & Davis, I. S. (2008). Proximal and distal influences on hip and knee kinematics in runners with patellofemoral pain during a prolonged run. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 38(8), 448-456.

Willson, J. D., & Davis, I. S. (2008). Lower extremity mechanics of females with and without patellofemoral pain across activities with progressively greater task demands. Clinical biomechanics, 23(2), 203-211.

Souza, R. B., & Powers, C. M. (2009). Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 39(1), 12-19.

Lamontagne, M., Kennedy, M. J., & Beaulé, P. E. (2009). The effect of cam FAI on hip and pelvic motion during maximum squat. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 467(3), 645-650.

Zalawadia, A., Ruparelia, S., Shah, S., Parekh, D., Patel, S., Rathod, S. P., & Patel, S. V. (2010). Study of femoral neck anteversion of adult dry femora in gujarat region. NJIRM, 1(3), 7-11.

Fern, E. C., & Norton, M. R. (2010). Focus on femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Jt Surg, 1-6.

Powers, C. M. (2010). The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy, 40(2), 42-51.

McGill, S., Cook, G., & Liebenson, C. (2014). Assessing Movement: A Contrast in Approaches and Future Directions. Movement Education Group.

Rippetoe, M., & Kilgore, L. (2017). Starting Strength. Wichita Falls, TX: Aasgaard Company2005.

Willy, R. W., Hoglund, L. T., Barton, C. J., Bolgla, L. A., Scalzitti, D. A., Logerstedt, D. S., … & Beattie, P. (2019). Patellofemoral pain: Clinical practice guidelines linked to the international classification of functioning, disability and health from the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 49(9), CPG1-CPG95.

Facts and Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved February 25, 2020